Changing Food Consumption Patterns in China

chinagate.cn, June 12, 2014 Adjust font size:

In a recently released World Bank report, a special topic on changing food consumption patterns in China discussed its implications for domestic supply and international trade.

Rapid economic growth has changed Chinese diets—amount, quality, and composition—and will continue to change them for a while yet, as many more consumers shift their diets from crop- to livestock-based products and away from basic staples. Such a shift to a more “affluent” diet is adding strains to agriculture because production of livestock-based food requires far greater resources and causes more environmental damage than that of vegetable-based food. These factors will start to constrain the country’s food-output capacity and availability over the coming decades unless tackled now—hence the need to understand how China’s domestic demand for and supply of food will evolve, as a basis for formulating policy.

Higher incomes have changed food consumption patterns

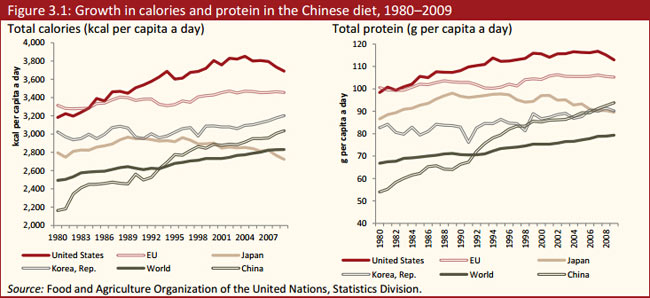

China’s rapid economic growth since the market-oriented reforms launched in 1978 has vastly improved diets. Total calorie intake per capita a day has climbed by nearly half, from 2,163 kcal in 1980 to 3,036 in 2009. This is much faster than the world average, which grew from 2,490 kcal to 2,831 over the period (figure 3.1 left panel). Calorie consumption is now roughly the same as in Japan and the Republic of Korea, but still lower than in the United States and the European Union. Protein intake, too, climbed sharply, nearly doubling from 54 g per capita in 1980 to 94 in 2009 (figure 3.1 right panel), with about three-fourths of this growth coming from livestock-based products. Fat intake nearly tripled from 34 g per capita to 96 over the period, again largely based on greater consumption of livestock products (about two-thirds). Calorie intake among some high-income countries, notably the United States and Japan, has declined somewhat over the last decade or so.

The majority of the increase in calories sourced from crop and livestock products in China, as with protein and fat, has come from livestock products. The calorie intake from crops has been relatively steady at around 2,300 kcal since the early 1990s. Calorie intake seems unlikely to rise dramatically but dietary patterns are likely to adjust further as consumers increasingly source their calories from livestock products that require far more resources per kilogram of food consumed. This continuing shift will raise further the resources required to meet China’s food demand for an extended period, adding pressure to world food production, as upgrading diets based heavily on livestock products requires much larger increases in agricultural resource use measured in cereal equivalent.

Growth rates of consumption and of output are likely to be broadly comparable as incomes grow to around USD 20,000 in purchasing power parity terms. After that, it seems likely that consumption growth will slow relative to production and the gap between supply and demand will begin to close. This is, however, a tentative scenario. If, for instance, China slowed its investment in agricultural productivity, or climate change cut productivity, the gap between supply and demand might increase.

China is also in a very different situation from some neighboring economies, such as Japan or Korea, whose much smaller land endowments per person suggest that continuing large net imports are likely. International comparisons reveal striking differences between countries in the extent to which food imports as a share of total consumption have evolved. For rice, wheat, corn (maize), and soybean—together “grain”—most lower income countries have maintained close to 100 percent self-sufficiency, but this ratio has declined sharply in higher-income East Asian economies (Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, China). China, given its larger per capita land endowment, seems unlikely to follow their path, no doubt retaining much higher aggregate self-sufficiency in grain.