Climate Change 'Takes Toll' on Grain Harvest

Adjust font size:

Climate change will trigger a drop in China's grain harvest over the next few decades and threaten food security, a leading agriculturalist warns.

Tang Huajun, deputy dean of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), said a 5 to 10 percent crop loss is foreseeable by 2030 if climate change continues.

"The impact of climate change, coupled with arable land loss and water shortages, will cause a bigger grain production fluctuation and pose a threat to reaching output targets," Tang told China Daily.

China, which recorded a grain output of 530.8 million tons in 2009, plans to increase output to 550 million tons by 2020 to ensure grain security for the world's most populous country.

However, China is likely to face an inadequate food supply by 2030 and its overall food production could fall by 23 percent by 2050, a previous report released by Greenpeace predicted.

"The output of the country's three main foods, rice, wheat and corn may suffer a 37 percent decline in the latter part of this century if the government fails to take effective measures to address the impact of climate change," Tang said.

He based his prediction on a study of the climate-change impact on China's grain production over the past 20 years.

Tang said that the government had asked his academy to launch a five-year research project to monitor the impact of climate change on grain production.

Under the project, launched in September, a total of 11 field observation stations have been set up in the major grain-producing areas in the northeastern, northwestern and southern parts of China.

"Agriculture has been the worst hit by climate change and some negative effects have become more obvious due to rising temperatures and water shortages over the past 10 years," Tang, chief scientist for the research project, said.

Drought is the biggest threat to China's grain harvest, causing an annual average loss of about 15 to 25 million tons from 1995 to 2005, or 4 to 8 percent of the country's annual output, he said, citing official statistics.

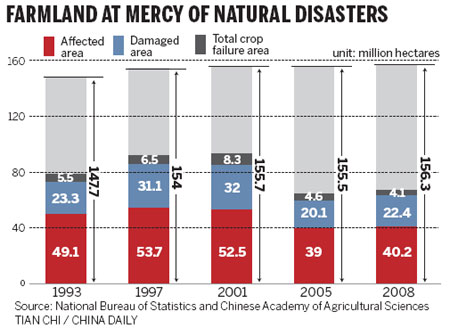

Other weather-related natural disasters such as floods, hailstones and typhoons have also taken a toll on grain production, Tang said.

Yang Peng, a researcher with the CAAS, told China Daily the production of wheat, which is more vulnerable to extreme weather, has suffered worst from climate change.

In north and northeast China, farmers are now planting less cold-resistant varieties of wheat due to rising temperatures over the past decade.

But because extreme weather, such as freezing temperatures, has become more frequent, wheat output has decreased, Yang said.

Experts predict that the climate will lead to a change in the planting locations of the three main foods.

Rising temperatures have caused the planting area for winter wheat to shift north by up to 200 kilometers, Tang said.

The rice planting area has also increased significantly in the three northeastern provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang due to rising temperatures.

The rice yield in the three provinces accounted for 13 percent of the country's total rice output in 2008, an increase of three percentage points over 1984, Tang said.

(China Daily November 5, 2010)