Documenting lives of Chinese female migrant workers

China.org.cn by Zhang Lulu,March 06, 2018 Adjust font size:

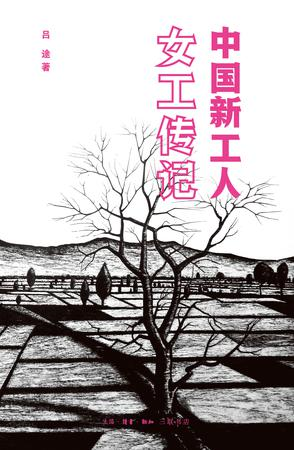

Author Lyu Tu has been studying and training migrant workers for more than 15 years. "Chinese Migrant Workers: Biographies of Female Workers," published in November 2017, is her third and latest book on the subject. The book documents the lives of 34 female migrant workers she interviewed from 2010 to 2016. China.org.cn spoke with Lyu about her new book, the women she talked to – who are between 24 and 67 years old – the changes the group went through over the years, as well as their work, love and longing. The interview has been translated from the original Chinese and edited for brevity and clarity.

China.org.cn: When did you first begin studying Chinese migrant workers, and what brought them to your attention?

Lyu Tu: It was back in 2003 when I was in Indonesia. Fresh from my Ph.D. study, I was part of an international study program on social changes in four Asian countries, including China. As the leader of the China group, I was free to choose whom to study. I thought at that time, migrant workers were vitally important in China because of the huge size of the group and the urban-rural mobility that is not only bound to change their lives but also the entire society.

China.org.cn: Your previous two books are about the Chinese migrant workers as a whole. Why did you choose to focus your latest work on female workers?

Lyu: As a woman myself, I have many experiences that keep changing over time, and my role changes too. I believe the more sufferings and setbacks a person experiences, the better she understands herself and the world. For female migrant workers, they encounter more difficulties in their work and life, which I believe lead them to more experiences and thoughts about life and the world.

My master's study is on women and development. As a student at the time, I had almost no clue about the real problems facing women. However, over time, I began applying theories on practical problems, and my academic background helped.

Most importantly, they are doubly disadvantaged being women compared to the men, and being migrant workers compared to other social classes. It is not because they are the least privileged that they warrant our attention, but because they have much potential, vigor and vitality, which is prevented from development.

We have been searching for solutions to the migrant workers' problems for years, but unfortunately to no avail. Some workers say the only way out for them is to become bosses themselves, but in fact and paradoxically, the bosses and the exploitative employment system are largely the reasons why they are in such plight. I believe the poor people need to team up and help each other. Though this book is about female workers, it is intended to find possible solutions for all the migrant workers.

China.org.cn: You said in the book you interviewed about 100 female migrant workers, but eventually the book includes stories of 34 women. How did you choose the 34 stories? Whose stories were you most impressed with?

Lyu: I chose to talk to ordinary people, not heroic role models so to speak. But of course, the women I write about have accomplished something that make them special in one way or another.

For instance, two groups of female workers I talked to in Guangdong province were originally commonplace cleaners laboring away, but they had to fight for their rights after their younger and more articulate co-workers were fired. They grew into extraordinary figures along the way.

I tried to interview women workers from different age groups, ranging from those born in the 1960s to those born in the 1990s. I also tried to talk to female workers who have changed themselves through actions. It is not necessarily that they became famous or gained material success, but they have had some extraordinary experiences unique to themselves, and they are conscious of the changes.

I am most impressed with one of the female workers whose name is Hui. The 50-year-old woman stood up to her employer who had failed to pay for her social insurance and vigorously debated with the factory union. But she brought me more emotional impact than that. She was madly in love with her elementary school classmate ever since they were young, but she did not end up with him. She was saddened by this. Many people find it hard to imagine romantic stories like this with migrant workers, but they are actually capable of such love and romance as others, and I believe that people are after all the same in terms of love, emotions and sentiments. This is also one of the reasons why I write the biographies of female migrant workers: I think any sensible person who read stories like this will come to realize that migrant workers are also capable of deep feelings, and hopefully they will be moved by their stories and respect the lives of migrant workers.

There is another facet to Hui's story. When she found out her husband cheated on her, she decided to cheat on him in revenge. But when she actually did that, she realized this did nothing but hurt herself more. When other men approached her later, she rejected them, saying she would not be "used as a public toilet." Her determination was not driven by the traditional notion of "being loyal to your husband," but because of her self-respect and self-esteem.

China.org.cn: The female workers you interviewed are born between 1951 and 1994, spanning more than four decades. Are there any major differences between the age groups and any changes of the entire female workers group over the 40-odd years? Are there any changes in these workers' employment, right to residence and their children's access to education – ways from which you examined them in your previous two books?

Lyu: They do exemplify differences among different age groups. Older female workers were born in more difficult times and are hence happy to have found a stable income. They compare their lives with those of their parents' generations and find themselves content.

The younger workers are different. They were born when China was much better off, and they are not short on food or clothing. They often compare their lives not with their parents', but their peers' in the city. If they are not happy with their work, it is perhaps because they find it boring.

Also, times change. In the 1990s, China was the "world's factory" and saw its economy boom. Now, the country is in the process of industrial transformation, bringing with it various work options. Thus young people, including migrant workers, want more things from their work. I know some migrant workers from the organization I am in (a Beijing-based NGO on migrant workers) who refuse to work in factories due to the long hours, because they say they would read and write at night.

As to residence status, it is different too. Few of the older generations of migrant workers would choose to buy property in the cities. Instead, they are able to buy or build houses in their rural hometowns. As for the younger generation, though their wages are higher than the older generations, they actually are not better off because of the faster increases in the consumer price. The conditions in their rented homes may be better, but they might not be able to buy or build houses in their hometowns as their parents' generation do.

When it comes to their children's education, I find that younger female workers tend to care more about their children. But the access to education is different in different cities. For instance, in Beijing where the number of schools for the children of migrant workers is shrinking, it is becoming more and more difficult for the children to attend schools around where their parents are.

In other cities, for instance Changsha, I heard that many students in a public school I visited were children of migrant workers. And in Shanghai, about 60 percent to 80 percent of migrant workers' children can attend public schools, but I'm not 100 percent sure about that as there is no official data.

China.org.cn: Do you think the women workers in your book love their job? What do you think they want from their work?

Lyu: I don't think they are passionate about their job, but they can perform well on what they are told to do. Female workers that I talked to have different attitudes towards their work. As I mentioned before, those who are born in the 1970s are not quite into their work, but they can be very patient, as they have to help support their family.

It is different when it comes to those who are born in the 1980s. Their careers began in the first decade of this century, when many things are drastically different from the past. They tend to compare their work and life with their peers from the cities, and realize the wide gap between the rich and the poor.

They can also be susceptible to various ideas in society. Of course it is not like that the younger generation don't care about wages, but they will actively choose whom to work for. If they do not like their jobs, they would not take them.

I talked to a worker named Wang Qi, who used to work in a factory that produced mobile phones. She told me she did not like her job, and she liked photography. So she saved up money to buy photography books and even a camera. She did not just want a paycheck, but aspired for more. She now works for an NGO in Tianjin.

China.org.cn: Some of the female workers you interviewed are now engaged in not-for-profit organizations or work for the public good. What do you think motivates them? What changes can they bring?

Lyu: As I said before, many migrant workers do not like their work, but they have no other options. So the first time they get to know public benefit work, they often become very impressed. But their commitment to such work does not come easy, because most of the organizations are cash-strapped and don't offer desirable wages, and the prospect of positive changes can be dim. Still, migrant workers highly acknowledge NGO work, as it can broaden their horizons, raise their abilities as well as offer them recreational activities in their humdrum lives.

China.org.cn: You worked with migrant workers for 15 years. How have you interacted with them as a scholar? Do you think the contemporary Chinese society has paid adequate attention to migrant workers?

Lyu: My work with migrant workers comprises of three parts: research, training and action. When I first began the work, I found there were not many books that can offer practical guidance and advice on helping migrant workers. I am convinced that the society is an integral whole, and if intellectuals are too removed from reality, their knowledge may be of no use. Personally, I want to do something that can bring about change.

I don't think the academic community has done enough in regards to migrant workers considering the severity of the problems. However, it is a positive trend that increasingly more people are paying attention to the problems. Still, migrant workers -- and other groups too -- should also be more introspective; they should not fall into the popular value system that prioritize money, cars, houses and so on.

China.org.cn: What do you think is the ideal scenario for migrant workers in future?

Lyu: Migration or mobility is not necessarily bad, if you choose to migrate at your own free will. In my first book, I describe the current situation for migrant workers as without an anchor: "The cities where they can't settle down in, and the villages where they can't go back to." A promising scenario will therefore be for them to be able to find a home in both cities and villages.